This is a long post about a short cruise with a twist at the end.

Getting out of the Bay and up or down the coast some distance has been on my punchlist for some time. It wasn’t a perfect time, but I don’t suppose it ever is, so the second week of February I took a couple of days to head down to Half Moon Bay. The harbor at Pillar Point is about 25 miles +/- from the Golden Gate Bridge.

I passed another Ericson on my way out of Richardson Bay. I screamed, “Ericson!” “The Best!” came the reply. I viewed this as good omen.

SV Archangel

The timing was good on the way out. There was an ebb tide pushing me under the bridge into the Pacific and a little wind to help get me out around Mile Rock. I was doing nearly 5 knots with only 8 of wind.

I got out around the Cliff House and the wind picked up. I set up the Aries and did some clickety-click tuning.

Soon enough we were ripping. The radio was full of political news. I turned it off. I turned off the instruments. The vane was working and I was zipping along at what I call hull-speed with the boat driving itself entirely mechanically, in near silence.

I have found that everyone who has a mechanical windvane comes to write about it as if it were a steady friend, and it’s easy to feel this way. Properly set, a vane feels as comfortable as a slowly-swaying hammock. Moving a little side-to-side, but always coming back to centerline. Six in sixteen, full sail plan, look Mom, no hands. Magic. I went below and tried to imagine sleeping at six knots.

I was between one and two miles offshore, in 50-70 feet of water. In February off Ocean Beach it turns out this area is a minefield of crab pots. They came in series, usually 7-10 traps, parallel to the coast. I could imagine the fisherman dropping the pots one after another. I swerved and dodged. I didn’t want prop blade entanglement.

The strong beam-reach wind faltered after an hour or so and dropped back into the varying single-digits. I pushed south past Fort Funston of hang gliders, where I bring my kids and my dog to run around. Past Pacifica where the most beautiful Taco Bell in the world overlooks the surfing beach at Linda Mar. Out around San Pedro rock.

Mid-afternoon settled, and I wanted to arrive at Pillar Point well before sundown, and so I rigged the Yanmar sailplan. I mean I turned on the engine. I motor-sailed down Pedro Point, past Montara and Moss Beach. The propeler whirled and I continued to dodge crab pot buoys.

The approach to the Pillar Point harbor is not complicated, though depending on the swell, the area on the point can take on its other more public persona. This is the site of the the Mavericks surf break. The night before, I had some visions of how my approach could go badly.

Fortunately, the swell was limited and there was no danger of sending my boat down a triple-overhead crushing wave.

After rounding the point at Mavericks, the approach channel marker requires one to travel well south of the mouth of the harbor, to avoid an outcropping of shallow rock that extends southward into the water. I was careful, and headed round and motored into the harbor.

I found dozens of empty mooring balls in the outer harbor and after some flustered back-and-forth, managed to tie up to one of them. I brought the main down and furled the jib. Straightened up the cockpit some, and then into the cabin.

I settled into my new situation relieved and paused to enjoy the still sounds of the birds and the wind. The lights of Half Moon Bay came on up the hillside. It took some time for the insistent toot of the harbor entrance horn to fade into the unrecognized background.

While I had tested the boat stove earlier in my ownership, I had never really prepared a meal in the galley. I started puttering around and suddenly something magic happened. I turned on one of the galley faucet valves and hot water came out of the spigot! I had been convinced until this point that my hot water heater did not work or was not connected properly. But lo and behold, after sixty minutes of motoring, hot water came forth from the tank. Wonderful news.

I prepared an amazing dish brimming with scents of the subcontinent: chickpea masala and Madras lentils. Of course, when I say prepare, I mean that I poured out the contents of two Ultra High Temperature pasteurized pouches that I bought at Costco, into a pot. Further diversifying the concoction, I added some pieces of black pepper Spam. It thought it would bring me good Polynesian karma. What the dish lacked in visual presentation was more than made up by ambiance and context.

Before I sat down to eat, I heard the low burble of a diesel engine approaching. It was the harbor master’s boat and the two gentlemen aboard gave me the once-over. “Normally we charge $10 for a mooring ball, but well, when are you leaving?” “Tomorrow morning!.” I would have gladly handed them a ten dollar bill. I think it would have been more of a hassle for both of us, so they just waved me off for next time. Anchoring would have been free, they said.

After enjoying my meal and face-timing with my wife and kids, I retired to the capacious double-berth master stateroom at the rear of my 200-series boat. I did some jumping jacks and windsprints in the space, eventually sprawling out for a wonderful night of rest.

The wind picked up at a couple of points overnight, and sang in the rigging. The harbor breakwater ensured still water, and with the sails taken down, the boat merely wandered here and there around the mooring. I slept like a log.

The next morning was overcast and the air was still. I have recently purchased one of those newfangled flying cameras and practiced a couple of times with it. Given how still the air was, I thought it would be worth a test flight out of the cockpit. This sequence was the best I managed.

I landed the drone back in the cockpit (and not in the harbor!) and declared victory.

Breakfast was weak coffee and sugary instant oatmeal. Again, delicious. I decided that I need to develop a work-flow for dealing with dirty dishes and the kitchen generally. Things needed cleaning, and a more complete inventory of what I have and need would be of benefit.

My plan was to head back up to San Francisco, and ride the flood tide back into the Golden Gate in the afternoon, opposite the ebb I rode out the previous morning on my departure.

I motored carefully out of the harbor around 9:30am and then past the channel to the open ocean. There wasn’t much wind. I started the engine and pointed north, wending my way up around Pillar, then Pedro Points and up into the minefield of crab pots. I didn’t feel great, with a bit of a headache. Perhaps I need to clean out my fresh water tanks somehow. I think I was a little reluctant to drink too much of the water, which may have left me dehydrated.

Several (4-5) hours of plodding up the coast later, I came around the north end of Ocean Beach and faced the Golden Gate. I was earlier than originally intended for my flood-tide sail plan and I was heading into a 2.8kts ebb current. I had the wind at my stern, which was helping, and I left the engine on, but I was still only making a little over three knots of progress toward my home port, and this felt inadequate.

The Golden Gate Bridge is constructed over a bottleneck or choke point of the narrowest gap between the entry to the bay. As one might imagine, when water rushes out in an ebb tide (or in on a flood tide) back currents form like an eddy in a river. I knew that if I could just duck into the back-flowing current, I would turn the ebb tide to my advantage, and sure enough, it worked.

On the south side of the entrance, the major marker is Mile Point Light, an unmanned lighthouse guarding a nasty rock protruding into the entrance. I got around the light, carefully. I went from three knots of fighting headlong into the ebb, to six-and-half, coasting up along Baker Beach, still with the wind behind me on a deep reach, and the motor on, and now the backflow too. Coasting along.

I have mentioned this elsewhere, but I spent time as a younger person as a professional whitewater raft guide, and feel like I can pick out these currents and routes as well or better than the average bear. After all, isn’t a little thirty two foot boat the best kind of craft with which to go sneaking up a coastline? I approached the south tower of the Golden Gate Bridge, pleased as punch. On my Navionics chart on my plotter, I could see some rocks marked, but none in my immediate vicinity.

I was preparing at the last moment to cut out of my beneficial back-current and dash north across the Gate to Sausalito. Pride goeth.

When the bottom six inches of the lead keel of a fiberglass sloop hit an immovable object like a rock, the keel turns into a lever. The front of the keel tries to pull itself out of the boat. The back of the keel tries to shove itself up into the boat hull. The hull resists, and the bow of the boat begins to dissipate forward-movement energy by burying itself into the water. The boat kicks forward to 22.5 or perhaps even 30 degrees. The forestay transfers diving tension to the masthead and then down the backstay to the stern of the boat. The immediate motion of the boat ejects the helmsman from his seat, hovering 18” over the wheel. With the boat diving nose-first into the sea, one is afforded a moment of weightless reflection.

My thoughts came in nanoseconds, in something like this order:

First: “Rock.”

Second: “Vilhauer, you fool. You dilettante clown! You’ve invested a whole year of your life into this boat and you haven’t loved a physical thing this much since you were fourteen and saving for a mountain bike and now you have gone and ruined the whole thing in an instant, and for what? To get home a little earlier? To feel like you were being somehow clever? You damned fool.” There was considerably more profanity, which I will spare you.

Third: “Get your act together, dude. Are we driving out of this situation, or are we swimming out of it?”

I landed on the wheel and crumpled to the floor of the cockpit. The boat ground off the rock.

Quick assessment. Did the engine still work? The Yanmar engine purred unperturbed, though I could have sworn it muttered, “Stupid Gaijin.”

Rudder check? Rudder working. Edson wheel still operational. I didn’t bounce the rudder.

I have hinged doors on my companionway and I peered down into them and did not see any water lapping up through the floorboards. And if I had, what would I have done? Turn on the bilge pump, I guess. The nearest harbor where I could have tied up would have been the Travis Marina at Horseshoe Bay, a great little nook on the north side of the bridge. I didn’t really consider it, frankly. I just wanted to get back to Sausalito.

I pointed the boat north and I carried on, with engine and still full sails against the ebb. What I should have been doing all along. I kept peering down into the cabin to look for water on the sole. I made it back to Sausalito and into my slip.

I was pretty rattled by the grounding, and had not left the cockpit after it happened. It was only when I arrived in my slip to tie up and re-group did I realize that when I struck the rock I catapulted my anchor out of the bow roller. The anchor stopped reeling out when the tie-off from the chain to the rode tangled on the anchor locker door. I had, off the bow of the boat, dragged the anchor and 25’ of chain across the Golden Gate and through the mud flats of Richardson Bay.

I placed my first call to the boatyard to see about a haul out. I was perhaps excessively cavalier in the message I left. “I’ve just umm, kissed a rock and I wanted to see how much lipstick it left.”

A couple of messages back and forth and they suggested I have my diver go down and have a look. Checking over my left and right shoulders, seeing no divers and only a mirror in front of me, the next day I donned my wetsuit and brought a GoPro.

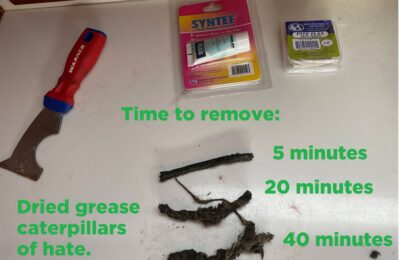

Well sure enough, Vilhauer. Quite a chunk.

I went home and was glad I had paid my insurance renewal on time. I called down to the boatyard and explained that my diver had indeed found some real damage. On Friday we scheduled the haul out for Monday morning.

I cleaned the keel bolts over the weekend and inspected the bilges. I got as much of every drop of water and piece of dirt out as I could. There was a trickle of water coming into the bilge, but given a couple of overnight tests, it was not any more than my previously poorly-adjusted prop shaft packing gland.

There are six large keel bolts in my 32-200. The forward one connects through the hull alone, while the aft five span the TAFG (Tri-Axial Force Grid structural reinforcement) and the hull. I did not find evidence of any new cracking of fiberglass around the bolts.

Monday morning came around and after waiting my turn, we put Sure Shot up into the slings at KKMI Sausalito. The damage didn’t look any better in the light of day.

“Man, the poor rock!” they said. I concurred. I really knocked the heck out of it.

The keel edge repair would be pretty easy to fix. More preoccupying is the keel-hull joint and the forces at work there.

Forward leading edge

Aft, trailing edge

That the keel flexed up into the hull and broke off the layers of paint is clear. There are some fiberglass fibers exposed at the joint apex.

I’ll write another note with more forensic analysis as it becomes available, but at this point the greatest concern from the KKMI guys (who, FWIW had about 3 other keel-strike hulls hauled out the same time) is that the compression of the trailing edge of the keel could have de-laminated the TAFG from the hull in this area, and that structural weakness needs to be repaired at all costs if Sure Shot is to remain a going concern.

Pulling the mast and dropping the keel is a given for a repair. I’m planning some additional lower-cost forensic work for early this week to get more information as I begin negotiations with my insurance carrier.

It really was a great first-cruise, except for the end part.